The Soviet Union stopped jamming BBC Russian-language broadcasts in the summer of 1963, a month before I joined the department responsible for writing and delivering them. During the five years I worked at Bush House, for decades the home of the BBC World Service, citizens of the USSR were able to listen to our programmes free of electronic interference. The only limitations on audibility were the power of the BBC's transmitters and ionospheric conditions. The targeted audience could, by and large, hear us, but were they listening; were we having any impact; did they feel informed about life in Britain?

Apart from clear evidence that Soviet youngsters were as keen as the rest of the world on British pop music, not much could be gleaned from the four or five letters we received most weeks. Reports by individuals returning from trips to different regions of the Soviet Union led to claims that listenership at any one time may have been as high as ten million. Anecdotal evidence spoke of Muscovites keeping schedules of times and wavelengths of our transmissions: more than four hours of programming spread across day and night. But was it just the Beatles they were looking for? If we feared that few in the USSR were paying us serious attention, the Svetlana Stalin letter affair of May 1967 made it abundantly clear that we were wrong. The Soviet authorities may no longer have been jamming our programmes, but they were perfectly prepared to blackmail the British Government to prevent the Corporation from transmitting to the USSR one controversial talk.

Most clashes between the BBC and the British Prime Minister of the day have been well documented. Those relating to the 1926 General Strike, the Suez fiasco 30 years later, the 1982 Falklands conflict, and the May 2003 fracas over Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction rank among the best remembered. The 1967 Svetlana Stalin Letter Affair was widely discussed in the press at the time, and has been referred to in a number of later publications on broadcasting history, but my researches suggest that nothing has ever been disclosed about the protest of BBC colleagues and the brave act of justified insubordination by Alexander Lieven, Head of the BBC's Russian Service.

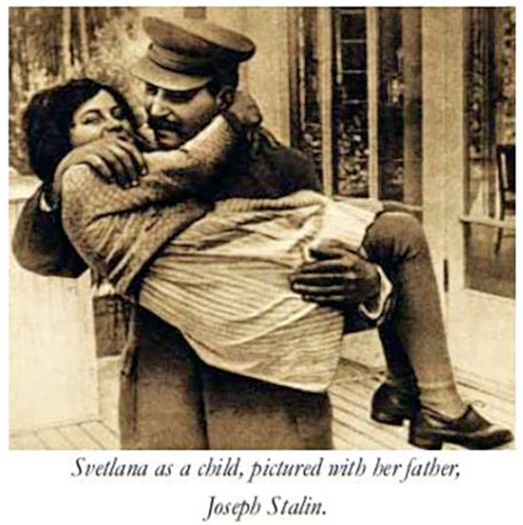

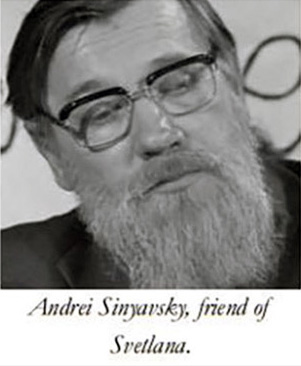

In April 1967, with official approval, Stalin's daughter, Svetlana, left the Soviet Union to scatter the ashes of her beloved Indian partner in the river Ganges. It rankled with her that she and Brajesh Singh had never been allowed to marry. Worse, they had been refused permission to seek treatment abroad when he fell seriously ill. Her disaffection from the Soviet system was deepened by the imprisonment (for publishing short fiction stories abroad without permission) of her great friend and colleague, the critic and author, Andrei Sinyavsky. It was no surprise, then, that she should seek asylum in the West. She turned to the US Embassy in the Indian capital, New Delhi, but to no immediate avail, in part because few Americans anywhere realised Stalin had fathered a daughter.

Even when Svetlana's identity was established, US President Lyndon Johnson was reluctant to grant her request for fear of antagonising the Soviets and embarrassing the Indians, who had steadfastly refused to take sides in the Cold War. But there was a willingness to help Svetlana leave India, 'quickly, legally and quietly', in the words of Ambassador Chester Bowles quoted by her in Tol'ko Odin God (Only One Year), the second of her three published autobiographical memoirs. Accompanied by a personable young CIA agent, she was whisked onto a plane to Rome, thence to Switzerland, where she was given a tourist visa for a six-week stay, on condition she kept a low profile and avoided communication with the media.

In Switzerland, hiding from journalists and paparazzi in Catholic convents, Svetlana read Boris Pasternak's novel Doctor Zhirago, which had been banned in the Soviet Union. It made such a deep impression that she felt compelled to describe her reaction in an unusual literary form, a letter written ostensibly to the author — who, as she knew, had died almost seven years previously. The 'letter' was published in the June 1967 edition of the American heavyweight journal Atlantic Monthly, the cover boldly proclaiming 'Reflections on Reading Doctor Zhivago: The First Published Work by Stalin's Daughter'. The translator was Max Hayward, who also co-translated (with Manya Harari) the first English version of Doctor Zhirago.

The letter is an emotionally affecting lament, the author glimpsing parallels between her own tragedy and that of Zhivago and Lara. Svetlana too had been separated from her children (22-year-old Joseph and Katya, 17). 'My beloved, long suffering, baffled Russia,' she grieves, where I have left my children and my friends to live our unbearable Soviet life'. Reading Pasternak's story, she conjures up an image of her dear friend, Andriusha Sinyavsky, imprisoned in the Gulag, 'standing barefoot with buckets of cold water in your hands, your hair unkempt and your clothes in rags'. She bemoans too the treatment she and Brajesh received from the 'Party hypocrites and Pharisees! … What could they know about us, how could they understand us, those miserable compilers of dossiers and denunciations?'

Two weeks before the June edition of Atlantic Monthly was due to appear, both the Russian and English texts of Reflections were telexed from New York to Bush House. BBC Archives have kindly copied for me a dossier, entirely in English, relating to what became the Svetlana Stalin letter Affair. It includes a memo signed simply 'James' and dated 17th May [1967], which was cabled to London along with Svetlana's article. From internal evidence, it is clear that 'James' was James Monahan, then Controller of the BBC's European Service, and, incidentally, Alexander Lieven's brother-in-law — Alexander's wife was James' sister, Veronica. James Monahan was writing to Lieven's immediate boss, Maurice Latey, Head of the East European Service. The memo explains the terms of the agreement with Svetlana, who thought so highly of the BBC's Russian language broadcasts that she was happy to permit this exclusive scoop. Monahan stresses that the BBC had 'committed to using the full text in Russian [underlining in the original] — that's why she's letting us have it'.

The Bush House hierarchy were not immediately keen to publicise what they had obtained. With one notable exception, those of us working in the Russian Service knew nothing of the coup our masters had brought off. The exception was Irina von Schlippe. An excellent interpreter, she had been invited to render into Russian, effectively on air, the first significant press conference given by Svetlana after her defection. She was therefore also the obvious person to voice Svetlana's article, and she recorded it secretly.

Our Soviet audience was first told of the existence of the item when it was trailed some 24 hours before the broadcast, scheduled for the evening of Thursday 25th May.

By this juncture, events on the international scene had intruded. On Tuesday 23rd May the world's press reported that Egypt had closed the Straits of Tiran (Gulf of Aqaba) to Israeli shipping, severing Israel's Asian supply route as well as blocking her access to Iranian oil. By international law, this was an act of war. British Foreign Secretary, George Brown, flew to Moscow in the hope of persuading the Soviet Union to use its influence to restrain the Arabs. Talks with Brown's counterpart, Andrei Gromyko, were under way when the radio trail for Svetlana's talk was heard in Russia. The Soviet response was as swift as angry: Brown was told in no uncertain terms that the BBC needed to cancel the Svetlana letter or there would be no further conversations at Foreign Minister level.

How the Svetlana Stalin Letter Affair developed thereafter can be learned primarily from a confidential, detailed memo written on 31st May by Charles Curran, the Director of External Broadcasting, to the only person higher in the Corporation staff hierarchy; the BBC Director General, Hugh Carleton Greene. Also relevant are the minutes of the BBC Board of Governors meeting of 31st May 1967. What follows is based on those documents, on my own recollections, and on consultations with Irina von Schlippe and other surviving BBC World Service colleagues of half a century ago.

At 1.30pm on Thursday 25th May, Charles Curran was informed that the Director General had received a phone call from the Foreign Office asking for the proposed broadcast to be cancelled. Otherwise, it might 'seriously prejudice the delicate discussions' in which the Foreign Secretary, George Brown, was engaged in Moscow. The Director General indicated his reluctance to 'consider such a cancellation'. Sometime before 2.40pm, the Foreign Office made a second representation to the Director General, with the warning that the Russians 'were standing by to resume full-scale jamming'. Having secured Curran's support, Hugh Greene again dug in his heels. Around 4.00pm, Curran heard once more from Greene, this time with the information that he had received a telephone call from Fred Mulley, Minister of State at the Foreign Office, who spoke from 10 Downing St with the authority of Prime Minister, Harold Wilson. Prime Minister was in full accord with his Foreign Minister in believing the Moscow negotiations 'involved the issue of war and peace in the Middle East', and he was 'prepared to speak to the Chairman [of the Board of Governors of the BBC] to urge on him the need to cancel plans for the broadcast'. In 1967, the Board was technically the BBC, and all staff, including the Director General, were subordinate to it.

Hugh Carleton Greene then had a change of heart and decided to recommend to the Chairman of the BBC Board of Governors, Lord Normanbrook, that the broadcast not go ahead. A statement was drawn up to explain why Svetlana's trailed article was not to be aired, 'so that the Foreign Secretary's efforts in Moscow to bring about an improvement in the international situation should not be prejudiced'. It made no mention of pressure from the British Government, so would have left our Soviet listeners to believe that abandoning the 'letter to Pasternak' was exclusively a BBC decision.

In a defiant act, Alexander Lieven went to the studio to deliver a significantly different statement. The descendant of an old aristocratic Russian family from the Baltic, Lieven was much liked and admired by colleagues and underlings alike. There was something of hero-worship in my own attitude to him. Only recently did I discover that he'd worked for the Security Services, but I was not at all surprised to hear of his proud boast that the spooks never discovered that in his youth he had collected money for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-9. On the evening of Thursday 21st May 1967, he risked his BBC career by announcing to Soviet listeners that it was 'at the request of the British Government' that the promised broadcast of Svetlana's article was not to happen. His dissident utterance concluded: 'We will inform you of further plans in connection with this broadcast as soon as possible', deliberately leaving open the prospect that the piece would be broadcast in the very near future.

In lieu of Svetlana's heartfelt lamentation, which revealed no state secrets and had very little specific political content apart from hostility to the Soviet regime, Alexander chose to put out music The Programme-as-Broadcast sheet (known to broadcasters as the P-as-B) indicates that two orchestral recordings filled the gap — Arnold Bax's The Garden of Fand and George Butterworth's A Shropshire Lad.

By this time, a group of us working late at Bush House had learned a little of what had been going on. I interpreted the use of music as a protest at governmental interference — a radio equivalent of blank spaces in other nations' censored newspapers. Whether or not inspired by Alexander Lieven's example, eight colleagues, including Irina von Schlippe and myself, penned and signed a memo to the Director General expressing our dismay at his decision to withdraw the promised broadcast, especially since it had been trailed 'not as a piece of Cold War propaganda but as a profoundly moving personal document of great literary value'. We expressed 'grave doubts' whether we could do our jobs properly 'if the contents of our programmes are to be in any way determined by our own or any other government'.

To his credit, Hugh Greene responded to our memo by hot-footing it to Bush House at the very first opportunity.

On Friday 26th May, Russian Service members were gathered to listen to his explanation of the background to the affair and the reasons for his decision. My recollection of his account tallies in essentials with what emerges from the dossier, though I'm not certain Greene told us about the Soviet threat to re-introduce jamming. In a nutshell, his justification for acceding to Harold Wilson's request was that, as Director General of the BBC, he could not claim to know better what was in the best interests of the country than the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary.

If, 50 years ago, I had been a braver and more quickwitted young man, I might have suggested to the Director General that the editor of The Times would probably not have yielded to government pressure as he had. After all, even though the BBC charter accords the Government the right to order the cancellation of a broadcast, the PM had not invoked that right. But even if Hugh Greene could have acted more boldly, I believe his position to have been entirely honourable. On retiring from the BBC in 1969, he published a memoir called The Third Floor Front: A View of broadcasting in the Sixties. Intriguingly, he makes no mention in it of the Svetlana Stalin letter Affair. I can only speculate on the reasons for the omission. Is it possible he felt remorse at not acting more resolutely to defend the Corporation's independence?

Foreign Minister Brown's meeting with Gromyko proved fruitless. War broke out on 5thJune 1967 between Israel and Egypt, Jordan and Syria, ending six days later in disaster for the Arab nations involved. I am sure I was not alone in doubting whether the Soviets had the kind of influence with Israel's Arab enemies that Britain's Government ministers imagined. In any event, Brown returned to London on Friday 26th May. That same day, Charles Curran wrote a memo to his boss, Hugh Carleton Greene, to tell him, among other things, that from his most recent discussions with Foreign Office officials it was now clear the postponed broadcast could take place. It was indeed transmitted the following day, Saturday 27th May, accompanied by a round-up of press comment on the affair, most of which deplored the Government's interference.

Several days after I left Bush House to take up a post in BBC Television, the Soviets resumed the jamming of BBC Russian Service broadcasts. They did so 30 minutes before Red Army tanks crossed the Czechoslovak border on 20th August 1968, putting an end to the Prague Spring.